Originally answered on Quora: What do scientists think of Daniel Amen and his SPECT scan diagnoses?

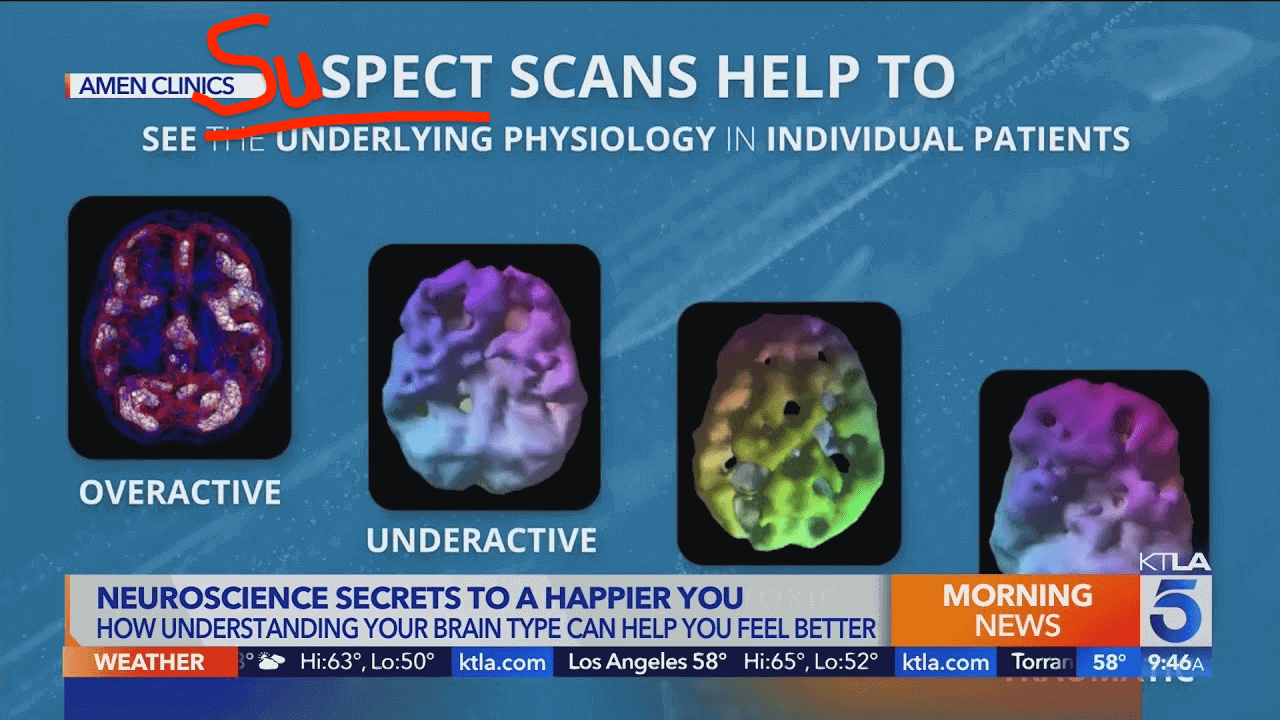

suSPECT

Dr. Amen is charismatic and he knows how to spin a story. His many assertions are taken at face value because he seems like someone that can be trusted, no? After all, he is “a physician, double board certified psychiatrist, teacher and nine time New York Times bestselling author.” He has also been a “Distinguished Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, the highest award they give members” and is “the author or co-author of 60 professional articles, seven book chapters, and over 30 books.” (These personal achievements were copied directly from his Quora profile.)

Someone with such a magisterial background would never make any unfounded assertions or advocate psuedo-scientific treatments, right? It’s a known fact that scientists have a full understanding of whatever they are talking about and what they believe to be true is above questioning by the less knowledgable and experienced. (I’m being sarcastic and facetious here.)

The fact is, scientists are wrong all the time (or perhaps a more accurate description is that they often find their hypotheses were only partly true). Refining theories and throwing out bad ones are just part of the scientific process. The danger comes when theories without enough scientific proof and rigorous testing are prematurely applied in clinical practice. Bad assumptions can lead to tragic outcomes, such as the numerous birth defects that were caused by giving thalidomide to mothers during childbirth. At the very least, these bad assumptions end up wasting time and money.

With respect to the practices of Dr. Amen, Dr. Harriet Hall has written a great article on this topic: Dr. Amen’s Love Affair with SPECT Scans.

Here is an interesting excerpt:

Psychiatrist Daniel Carlat wrote “Brain Scans as Mind Readers? Don’t Believe the Hype” in Wired Magazine, describing his own evaluation by Dr. Amen. Amen told Carlat his scans showed too little activity, a pattern of angst, and a predisposition to depression (that part was a slam dunk, since in taking a medical history Amen had already elicited the information that Carlat had had a short bout with depression). He recommended a multivitamin, gingko, less snowboarding, and more tennis. An expert at UCLA later reviewed the same scans and explained that the findings are meaningless because they haven’t been validated by controlled studies to determine their diagnostic specificity. Carlat likens Amen’s spiel to the cold readings of palm readers.

SPECT has limited temporal and spatial precision

Reading a SPECT image for psychiatric diagnosis is like trying to predict weather patterns from a single, static snapshot of the sky.

Will it rain later today?

The timing of the snapshot matters. The number of snapshots matter. The trajectories of the clouds over time matter. The field-of-view and resolution — these all matter for accurate weather prediction. Unless the condition is severe (e.g., storm clouds above), it’s difficult to predict whether it will actually rain today (perhaps New Englanders can attest to the unpredictability of daily weather).

Not at 5:40pm, but it will later!

SPECT imaging can take a snapshot of blood flow in the brain using radioactive tracers that bind specifically to brain tissue. The radiolabels are injected into the bloodstream and almost all are rapidly taken up by the brain within a minute. Areas with greater blood flow will contain more bound radioactive tracers. SPECT can be particularly useful for identifying seizure loci if the tracers are injected during an epileptic event. It has also been useful for identifying areas of possible brain damage/atrophy in Alzheimer’s and stroke patients. However, its use as a tool in the diagnosis of psychiatric conditions (e.g., ADHD, OCD, depression) is speculative at best. At this time, scientists have yet to identify reliable diagnostic biomarkers using more advanced tools such as fMRI, which affords both better temporal (~2 sec) and spatial (2-3 mm) resolution. The spatial resolution of SPECT is typically on the order of centimeters.

Will it rain later today? – SPECT version.

SPECT is costly and absolutely unnecessary for psychiatric diagnoses in otherwise healthy people

My greatest concern with respect to this issue has to do with the routine use of SPECT in perfectly healthy children and adults. Presently, any inferences of cognitive function gleaned from a SPECT scan for aiding psychiatric diagnosis can also be obtained by administering various scientifically validated neuropsychological tests (of attention, short/long-term memory, language, etc) and diagnostic inventories (e.g., Beck’s, Brown ADD, MMPI).

Moreover, not only is the procedure costly and unnecessary, it exposes oneself to radiation, which may lead to increased risk of cancer with repeated exposures. Often times you’ll hear that SPECT is equivalent to a chest X-ray. This statement is only partially correct. The radioisotope most commonly used in SPECT imaging is Technetium-99m, which emits predominantly gamma rays. The energy emitted by the gamma rays are approximately 140 keV, which is around the same ballpark as chest X-rays. While most of 99m-Tc will decay by emitting gamma particles, there is a minute probability that 99m-Tc will also release beta particles, which are especially high energy and can easily cause DNA damage.

Furthermore, while the energy of the gamma rays in SPECT and chest X-rays are similar, the dose of radiation over time are over two orders of magnitude greater in SPECT imaging. That’s well over 100 chest X-rays! A single exposure of gamma rays from a chest X-ray lasts only a few seconds. In comparison, the half-life of 99m-Tc is SIX hours. This means that it takes 6 hours for half of gamma-emitting 99m-Tc to decay to 99-Tc. Thus, long after the SPECT scan is over (30 to 60 minutes), the radiotracers in one’s body will continue to emit gamma rays for the next several hours.

Here are some tables for comparison (obtained from the Health Physics Society website):

[Report on radiation exposure from medical diagnostic imaging procedures]

The dose of radiation over time are over two orders of magnitude greater in SPECT imaging. That’s well over 100 chest X-rays!

As you can see above, it is misleading for any medical professional to call a chest X-ray and SPECT brain scan “equivalent,” which is actually common practice at the Amen clinics. Note, my aim is not to scare people away from medical imaging procedures involving radiation; an effective dose of 6.9 mSv is still relatively low exposure. In the United States, we receive about 3 mSv of background radiation every year. Other factors also contribute to the level of radiation exposure, such as the frequency of airplane travel. In general, we should try to keep our doses of radiation as low as possible. This means that we should avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures, especially when safer alternatives are readily available (and more credible).